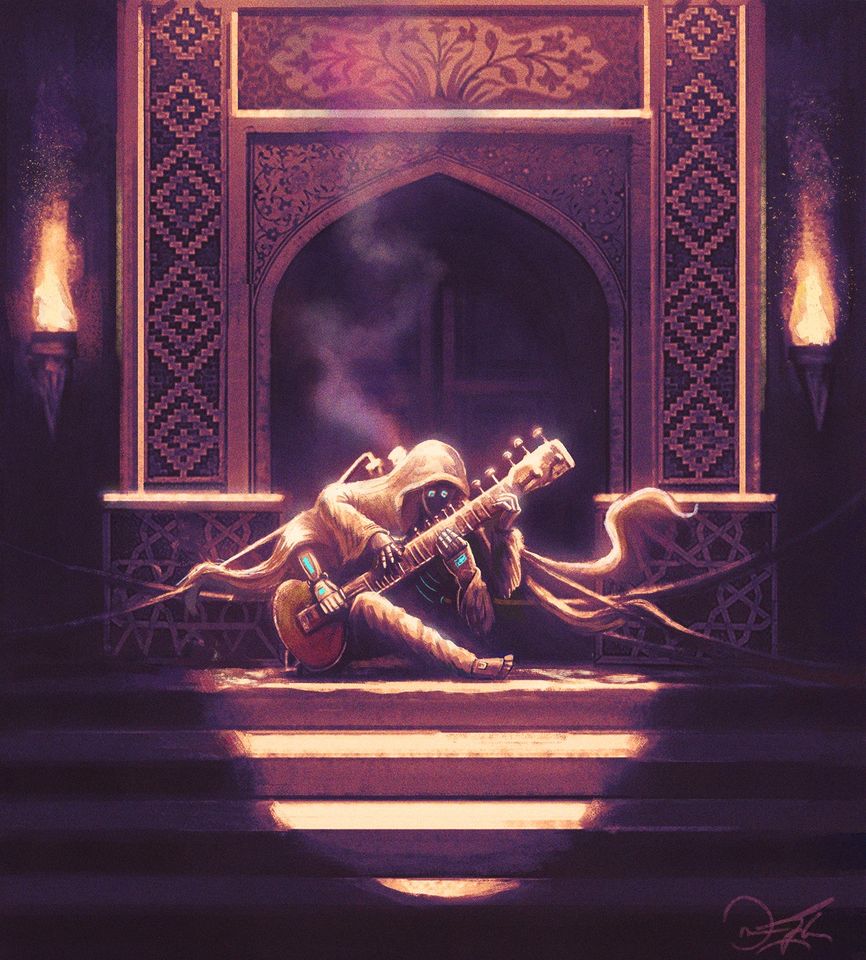

Omar is a concept artist, illustrator, and creative director. Originally from Peshawar, Pakistan, his formal training is in Engineering: he holds an MSc in Mechanical Design and an MPhil in Robotics. He was also pursuing a PhD in Robotics, but ultimately dropped out of the program to build a career better aligned with his passion for visual arts. He is a self-taught digital artist, and over the past eight years has worked as a visual designer and art consultant in a variety of fields, including corporate design, mobile games & apps, animation & film, and marketing campaigns, for clients such as Disney, Dreamworks, Save the Children, the British Council, and the United Nations.

He is also a new media fine artist, exploring art and design across emerging media like virtual reality, augmented reality, and projection mapping. His fine art work has been exhibited across Pakistan, as well as in London, New York, Seoul, Amsterdam, and Dubai.

The world of digital fine art

While many classically-trained artists have turned to digital art in the past decade, Omar Gilani began his work directly with digital paintings. Although he had always liked computers, the decision was mostly born out of necessity – in a small dorm at engineering school, Gilani didn’t have the space for the physical equipment that fine art requires. As time went on, though, he found that the digital work brought its own advantages, specifically in its flexibility for both creating and sharing work. He notes that “In Pakistan, if you don’t have an art degree and you aren’t affiliated with a university it’s really hard to break into the fine arts world.” He also found that working digitally allowed him to iterate quickly and to investigate multiple varieties of a single work, such as turning a painting into an animation.

At the start, Gilani says he applied to many galleries to exhibit his work physically, but was rejected outright as most people didn’t consider digital art to be real art. After gaining huge online popularity, however, he was approached for physical exhibitions and has since done shows all around the world. He has even sold work to collectors in the UK, despite the fact that “Most people don’t think digital art has that sort of value because it’s not a one-off piece of work, it’s a file on a computer.” Indeed, Gilani notes that the fine art world is based on the concept of scarcity, which is starting to appear in the digital world with NFTs (non-fungible tokens, a kind of cryptocurrency).

With experience in displaying works in both the physical and the virtual, Gilani has learned a lot about the intersection between the two. He notes that they have a lot of similarities with value based on scarcity and the uniqueness of the work, but that “NFTs have no gatekeeper to judge the value of the work and tell you what belongs on the walls of the gallery. If it looks nice, people will buy it.”

Of course, this year has accelerated the trend towards digital art. Gilani says that he did feel pressure to take advantage of the situation and create more but it was offset by the challenge of just living through such a time. Instead, he has taken the time to learn more about animation and 3D rendering.

Adapting to a post-reality world

When it comes to the idea of post reality, Gilani offers a pragmatic and optimistic perspective. “Making the distinction between reality and post reality assumes we know what reality is, whereas we don’t. Obviously there is a base reality that is shared, but we’ll never experience it in its entirety, because our experience is always going to be subjective. Right now we’re the first people dealing with this digital revolution, so we have to grapple with these questions because we’re seeing this change come about around us, but I feel like it’s just going to accelerate in such a smooth way that we won’t notice. Future generations won’t really care about this question that much. The virtual is becoming an extension of our experience of reality. What form that takes, what distinction there will be, and if that distinction is of any importance are questions that I feel will sort themselves out.”

As for the challenges that living in a digital, hyperconnected world pose, Gilani is of the opinion that people will learn by themselves to adapt, and that the benefits far outweigh the drawbacks. As long as people remain pragmatic with content consumption, mindful about time and attention management, and grounded in the real world with healthy lifestyles, the virtual world becomes nothing more than a useful, powerful, and meaningful extension of the space that each of us occupy.

On a final note, Gilani predicts that virtual art will just continue to develop and grow in sophistication. He does not think we have seen the final form of what it can be, and postulates that we will soon see a shift from the standard “page model” to 3D virtual spaces, and notes that “art will play a big role in shaping those experiences because all the digital world is created, and it’s going to need designers and artists to ensure that it’s an experience people gravitate towards.”